Task API (2 of 3) - Task API in-depth

- Introduction

- Background - threads 101

- Architecture - how?

- The AbstractTask class

- Lifecycle of a Task

- Monitoring Progress and Canceling tasks

- Package structure

- Dependencies and optional libraries

Introduction #

For a brief introduction on what the Task API is and how to quickly get started using it, read the first tutorial in the series - Task API - Quick Start Guide. This tutorial will go into lots of details on how the Task API works using the SampleApp shown in the first tutorial.

Background - threads 101 #

If you are not familiar with threading or EDT, then you can learn more about threads in the Concurrency in Practice book. You can learn more about the Event Dispatch Thread (EDT) in the Filthy Rich Clients book.

Architecture - how? #

If you are familiar with SwingWorker, then you will know that you work with it by creating a subclass (or anonymous inner class implementation) in which you define a doInBackground() method. Then you execute the task, and you have the option of canceling it. Instead of taking this approach of making inner class implementations in-line, the Task API works via a set of handlers and functors that you simply attach to a Task to tell it:

-

what to execute in the background

-

what to do when the task completes successfully, or fails, or gets interrupted.

You can also listen to bound properties (JavaBeans style properties) that will report status changes, progress updates, etc. It makes it very easy to work with the API, and if you’re used to writing event driven code, then this approach is very natural. There is a whole host of support classes that are provided to make your life really easy when working with these tasks - their functors, handlers, and listeners. I’ve worked very hard to make this API easy to use… it’s not a ‘lazy’ implementation on my part… I’ve worked very hard so that you don’t have to! :) . Another nice feature the API has is that it auto-cleans up resources, and auto-stops things, making it relatively easy to manage the lifecycle of these tasks and the resources & hooks (listeners, etc) that they consume. More on this in the other tutorials.

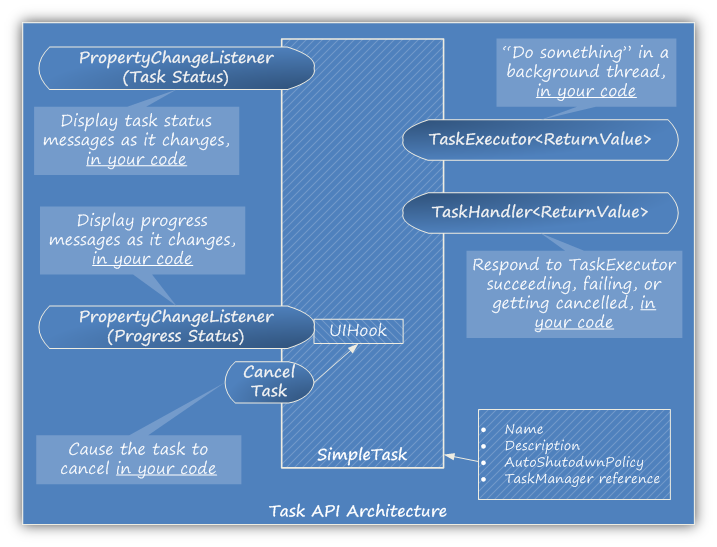

The following diagram illustrates the basic architecture of the API:

The AbstractTask class #

SimpleTask is a subclass of AbstractTask. AbstractTask provides most of the functionality that’s common between SimpleTask, NetworkTask, and RecurringNetworkTask. This includes:

-

Managing status listeners.

-

Binding with functors (TaskExecutor).

-

Binding with handlers (SimpleTaskHandler).

-

Functionality is also provided to interface with TaskManager - that allows the management and monitoring of these tasks.

Future tutorials will go into more details on all these new classes (NetworkTask, RecurringNetworkTask, and TaskManager).

All tasks can report coarse-grained-status information, and this is handled by attaching a PropertyChangeListener to the Task. Here’s an example of this:

_task.addStatusListener(new PropertyChangeListener() {

public void propertyChange(PropertyChangeEvent evt) {

sout(":: task status change - " +

ProgressMonitorUtils.parseStatusMessageFrom(evt));

lblProgressStatus.setText(ProgressMonitorUtils.parseStatusMessageFrom(evt));

}

});

The ProgressMonitorUtils class is provided to make it simpler to parse information out of PropertyChangeEvents, and in my opinion makes the code more readable and easier to understand (instead of having to remember to get the old value or was it the new value from the event?).

The functor (TaskExecutor) and coarse-grained-status information #

The TaskExecutor interface (TaskExecutorIF) has 1 main method: doInBackground(). This method is where you write your code that does “something in the background”. This code is guaranteed to run in a NON-EDT thread by the Task API. While it’s executing, it can report status updates, etc. to the Task, which are then propagated to any listeners that are attached to the Task. An adapter - TaskExecutorAdapter is provided which you can override just to implement the doInBackground() method.. It has other methods that you can override, which report coarse-grained status information to the Task (and it’s status listeners). Here’s the code for TaskExecutorAdapter:

public abstract class TaskExecutorAdapter<ReturnValueType>

implements TaskExecutorIF<ReturnValueType> {

public String getName() {

return "TaskRoot";

}

public String getStartMessage() {

return getName() + " started.";

}

public String getInterruptedMessage() {

return getName() + " was interrupted.";

}

public String getCancelledMessage() {

return getName() + " was cancelled.";

}

public String getSuccessMessage() {

return getName() + " completed successfully.";

}

public String getRetryMessage() {

return "Please try again.";

}

public String getNotOnlineMessage() {

return "Application is not online, did not run " + getName() + ".";

}

}//end class TaskExecutorAdapter

Except for the doInBackground() method, all the others really report coarse-grained status information to any Task status listeners. This information includes notification of when the task started, stopped, was canceled, encountered an error, etc.

The type binds a functor with it’s handler. If your doInBackground() method produces a return value at the end of it’s execution, then this value gets passed to the handler’s ok() method. More on this below.

Adding and removing status listeners #

The other half of this equation is the Task’s addStatusListener() and clearAllStatusListeners(). The add method is used to attach a property change listener that can receive coarse-grained-status information. The clear method is used to remove all listeners that are currently attached to a Task. Tasks try to clean up after themselves, so in case you forget to clear all the status listeners and you shutdown a task, it will clear all it’s status listeners for you!

Lifecycle of a Task #

The handler (TaskHandler) #

The SimpleTaskHandlerIF interface is a callback into your code that lets you know when a Task is going through it’s various lifecycle stages. Here’s the code for SimpleTaskHandlerIF:

/**

* TaskHandlerIF is an interface that encapsulates the various lifecyle

* stages that a task will go through. This allows task writers to add

* event handling code as a task progresses through

* various stages.

* <p/>

* Here's a quick rundown of the various paths that can be taken:

* <ol>

* <li>beforeStart -> started -> stopped -> ok

* <li>beforeStart -> started -> stopped -> error

* <li>beforeStart -> started -> stopped -> interrupted

* <li>beforeStart -> started -> stopped -> cancelled

* </ol>

*

* @author Nazmul Idris

* @version 1.0

* @since Oct 5, 2007, 9:59:16 AM

*/

public interface SimpleTaskHandlerIF<ReturnValueType> {

/**

* this method is called before the background thread is started.

* good place to do prep work if any needs to be done.

* this may not run in the EDT.

*/

public void beforeStart(AbstractTask task);

/**

* this is called after the task is started, it's not running in the

* background at this point, but is just about to. all the states have

* been setup (in the task) and updates sent out.

* this may not run in the EDT.

*/

public void started(AbstractTask task);

/**

* this is called after the task has ended normally (not interrupted).

* ok or error may be called after this.

* this runs in the EDT.

*/

public void stopped(long time, AbstractTask task);

/**

* this is called after the task has been interrupted. ok or error may

* not be called after this. this is caused by underlying IOException,

* InterruptedIOException, or InterruptedException.

* this runs in the EDT.

*

* @param e this holds the underlying exception that holds

* more information on the

*/

public void interrupted(Throwable e, AbstractTask task);

/**

* this is called after stopped(). it signifies successful task completion.

* this runs in the EDT.

*

* @param value this is optional. the task may want to pass an object

* or objects to the task

*/

public void ok(ReturnValueType value, long time, AbstractTask task);

/**

* this is called after stopped(). it signifies failure of task execution.

* this runs in the EDT.

*

* @param e this is used to pass the exception that caused the task to

* stop to be reported to the

*/

public void error(Throwable e, long time, AbstractTask task);

/**

* This is called after started(). it signifies that the task was

* cancelled by cancel() being called on it's SwingWorker thread.

* This is not the same as InterruptedIOException from the IO layer,

* which results in an Err.

* Cancel trumps: {@link #stopped(long, AbstractTask)},

* {@link #error(Throwable,long, AbstractTask)},

* {@link #ok}, and {@link #interrupted(Throwable, AbstractTask)}.

* <p/>

* In your handler implementation, just throw the results away, and

* assume everything has stopped and terminated.

* this runs in the EDT.

*/

public void cancelled(long time, AbstractTask task);

/**

* This method is called on the task handler when

* {@link AbstractTask#shutdown()} is called. It

* signifies that the task is going to stop.

*/

public void shutdownCalled(AbstractTask task);

}//end interface SimpleTaskHandlerIF

Instead of implementing this interface, you can use an adapter class provided to make it easier for you to create your own handler (SimpleTaskHandler). You don’t have to provide an implementation for each of these methods if you use this adapter. There are a couple of things to note when writing your handler:

-

Not all the methods in the callback are executed in the EDT, some are actually run in the background thread that’s executing your functor (TaskExectutor).

-

If you look at the documentation for each of the methods in the interface, you will find which methods are run in the EDT and which are run in the background thread.

This handler is intrinsically tied to the progress monitor and task cancellation described in the next section. There are a few different ways in which a Task can be canceled which causes the handler’s methods to be called (in your code).

The handler is also intrinsically tied to the functor, via the type that’s created by the functor and passed to the handler (via it’s ok() method).

Starting #

The Task API uses a SwingWorker under the covers to actually run your functor. This SwingWorker is managed by the API so that you don’t have to explicitly create one and control it, etc. A Task has lots of other resources attached to it (in addition to the underlying SwingWorker) like an object that allows task progress information to be reported to progress status listeners. This is called UIHook. This user interface hook allows status information to be reported to the UI and it allows the user to cancel the task at anytime, including any underlying IO operation that the Task is currently performing. More on this in the monitoring progress section. So, every Task supports progress monitoring and cancellation. To keep things simple, the following constraint is in place, only one underlying thread can execute at any given time. That is, if you run execute() on a task, then only 1 underlying SwingWorker will be created and executed. If you try and run execute() while a thread is already running then you will get an exception - TaskExeception. If you want multiple threads to run through your functor, there are many different ways to accomplish this. You can simply create more than 1 SimpleTask object and execute them with the same functor. Or you can create a RecurringTask and have it work on objects in a queue.

The reason for this single thread constraint is to make it simpler/easier for you to wire a Task up to a UI. It’s really simple to bind a set of listeners to one Task knowing that the background operation will provide status and progress updates to the UI. However, if this Task was allowed to spawn multiple background threads, then you would have to distinguish which one of these concurrent threads did the status or progress update come from, which makes things more complicated.

Stopping/Canceling and Shutdown #

Once you call shutdown() on a Task, it can no longer be started. You can cancel() a task execution (which will cause the underlying SwingWorker background thread to be terminated) and then execute() it again. However, shutdown() is a one time operation. Once shutdown() your Task is dead. In order to do be able to run it again, you have to create a new Task object and execute() it. Calling shutdown() causes all the status listeners, etc. to be cleared from the Task. So it cleans itself up when you shut it down.

Monitoring Progress and Canceling tasks #

One of the most important features that a Task has is the ability to report it’s progress to a property change listener that’s hooked up to it. It performs this by the use of a class called SwingUIHookAdapter. This class is responsible for broadcasting any progress status messages to registered listeners. It also keeps track of any underlying SwingWorkers that are currently executing and if the underlying SwingWorker is canceled, then it causes the UIHook to be canceled as well. So here are the different ways to cancel a task:

-

call cancel() on the Task, this will cause the underlying SwingWorker (if any is currently executing) to be canceled. This will also trip the SwingUIHookAdapter.

-

call cancel() on the UIHook itself. This will not cancel() the underlying SwingWorker - it causes an exception to be raised if any underlying IO operations are currently being performed via this filtered stream - InputStreamUIHookSupport. This filtered stream works very closely with the UIHook to ensure that everything is in sync. If you don’t use this filtered stream and call cancel() on the UIHook then it won’t really do anything.

So as you can see there are many ways to cancel a Task that’s currently executing. Which cancel() method you call depends on what you want to happen. Please note that a reference to the UIHook and SwingWorker (that’s currently running) is passed to your functor in it’s doInBackground() method. This is so that you can report progress status, and do whatever else that you need while your functor is actually running.

There are 2 types of progress messages that are sent - Send and Receive. The reason there are 2 types is because I wanted to accommodate IO progress. In IO, there is read operation progress (Receive) and write operation progress (Send). You can selectively enable or disable these types of progress status events to be propagated to your listeners via:

-

enableRecieveStatusNotification(boolean);

-

enableSendStatusNotification(boolean);

Here’s an example of how you wire a listener to get Send and Receive progress status updates (from the SampleApp’s _initHook()):

private SwingUIHookAdapter _initHook(SwingUIHookAdapter hook) {

hook.enableRecieveStatusNotification(checkboxRecvStatus.isSelected());

hook.enableSendStatusNotification(checkboxSendStatus.isSelected());

hook.setProgressMessage(ttfProgressMsg.getText());

PropertyChangeListener listener = new PropertyChangeListener() {

public void propertyChange(PropertyChangeEvent evt) {

SwingUIHookAdapter.PropertyList type = ProgressMonitorUtils.parseTypeFrom(evt);

int progress = ProgressMonitorUtils.parsePercentFrom(evt);

String msg = ProgressMonitorUtils.parseMessageFrom(evt);

progressBar.setValue(progress);

progressBar.setString(type.toString());

sout(msg);

}

};

hook.addRecieveStatusListener(listener);

hook.addSendStatusListener(listener);

hook.addUnderlyingIOStreamInterruptedOrClosed(new PropertyChangeListener() {

public void propertyChange(PropertyChangeEvent evt) {

sout(evt.getPropertyName() + " fired!!!");

}

});

return hook;

}

This is an example of how the UIHook is used along with the filtered stream in SampleApp:

GetMethod get = new GetMethod(ttfURI.getText());

new HttpClient().executeMethod(get);

ByteBuffer data = HttpUtils.getMonitoredResponse(hook, get);

Here’s the HttpUtils.getMonitoredResponse() method implementation:

/**

* can monitor an HTTP GET or POST response.

* make sure to release the connection once the POST/GET method is complete,

* using {@link HttpMethodBase#releaseConnection()}

*/

public static ByteBuffer getMonitoredResponse(UIHookAdapter hook,

HttpMethodBase method)

throws IOException, IllegalArgumentException

{

Validate.notNull(method, "method can not be null");

try {

InputStreamUIHookSupport is = new InputStreamUIHookSupport(

InputStreamUIHookSupport.Type.RecvStatus,

hook == null

? null

: hook.getUIHook(),

method);

return new ByteBuffer(is);

}

finally {

method.releaseConnection();

}

}

As you can see in this code, the InputStreamUIHookSupport needs access to the UIHook and an HTTPMethod or another InputStream in order to wire it up for progress updates. As the filtered stream reads data from the underlying InputStream, it fires off progress status updates, which are then propagated by the UIHook to any listeners. If cancel() is called on the UIHook, then it causes an IOException to the thrown and the filtered InputStream aborts immediately! This is a great way to stop any underlying IO immediately.

If your code doesn’t use the UIHook or filtered input stream, then calling cancel() on the Task will still work. However, if cancel() is called and you don’t check the isCanceled() flag of the underlying SwingWorker (passed to you in doInBackground()) to stop your code, then it will continue until it completes. The handler’s cancelled() method will be called immediately, but your code will continue to run. This problem arises from not having a stop() method in Java threads (having a stop() method introduces its own problems). This tutorial talks about this scenario in more detail. Not to worry, your handler will properly run and you will get a callback notifying you that the task is canceled.

Additionally, if you don’t have any underlying IO to monitor, and just want to send arbitrary progress messages, you can do so by using the following methods in the UIHook:

-

updateSendStatusInUI(int progress, int total);

-

updateRecieveStatusInUI(int progress, int total);

-

closeInUI();

These methods are normally orchestrated by the filtered InputStream, but you can orchestrate them manually in your code if you want to “fake it”. Calling these methods in your doInBackground() implementation will cause progress status messages to be propagated to any listeners that are hooked up to your Task’s UIHook object.

The topics covered here are not easy to understand or keep straight in your head. I recommend reading the Javadocs on the source code and looking at the sample code to make sense of all this. Again, if you don’t want to understand any of this, you don’t have to, if you just want to use the API.

Package structure #

There are just a few packages in the Task API:

-

Samples.* - this is where all the sample code is located. There are 4 samples, which correlate to the tutorials you are reading.

-

SampleService - this is a debug Servlet that has a GET and POST implementation that simply responds with whatever data is passed to the request. Good for testing.

-

Task.* - this is where all the major classes that you will use are located, like SimpleTask, the functor and handler adapters.

-

Task.ProgressMonitor.* - this is where all the progress status related classes are located.

-

Task.Support.* - this is where miscellaneous classes that are required to make the API work are located.

Dependencies and optional libraries #

When you download the taskapi.zip distribution you will find a lot of JARs in the dist/ folder and the lib/ folder. The dist/ folder contains all the JARs that you will need to include in your project, along with the taskapi.jar file itself. The lib/ folder is where these JARs are copied from (except for taskapi.jar, which is built from the code).

Here’s a listing of all these JARs:

| JAR | Required or not |

| AnimatedTransitions-0.11.jar | This is required to run the Samples. |

| appicons.zip | This is required to run the Samples. |

| commons-codec-1.3.jar | This is required. |

| commons-httpclient-3.1.jar | This is required. |

| commons-lang-2.4.jar | This is required. |

| commons-logging-1.1.1.jar | This is required. |

| forms-1.2.0.jar | This is required to run the Samples. |

| jaxen-core.jar | This is required to run the Samples. |

| jaxen-jdom.jar | This is required to run the Samples. |

| jdom.jar | This is required to run the Samples. |

| jide-oss-2.2.2.02.jar | This is required to run the Samples. |

| looks-2.1.4.jar | This is required to run the Samples. |

| saxpath.jar | This is required to run the Samples. |

| servlet-api.jar | Not required. |

| swingx-0.9.2.jar | This is required to run the Samples. |

| TableLayout.jar | This is required to run the Samples. |

| TimingFramework-1.0.jar | This is required to run the Samples. |

| TableLayout-javadoc.jar | Not required. |

| TableLayout-src.jar | Not required. |

| weather_icons_png.jar | This is required to run the Samples. |

| weather_service.jar | This is required to run the Samples. |

👀 Watch Rust 🦀 live coding videos on our YouTube Channel.

📦 Install our useful Rust command line apps usingcargo install r3bl-cmdr(they are from the r3bl-open-core project):

- 🐱

giti: run interactive git commands with confidence in your terminal- 🦜

edi: edit Markdown with style in your terminalgiti in action

edi in action